This timely passage is excerpted (pgs 53-54) from Thich Nhat Hanh's How to Smile Copyright © 2023 Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism on behalf of Parallax Press, Berkeley, California, www.parallax.org. Do not duplicate.

All though the following is not one of his poems, Thich Nhat Hanh's message strikes me as perfect for our difficult age.

Our World

by Thich Nhat Hanh

Many of us worry about the world situation. As

individuals, we feel helpless, despairing. The

situation is so dangerous, injustice is so wide-

spread, the danger is so close. In this kind of

situation, if we panic, things will only become

worse. We need to remain calm, to see clearly.

Meditation is to be aware and to try to help.

After the war, many people left Vietnam to

travel in small overcrowded boats across the

Gulf of Siam. Often they were caught in storms

or rough seas. People could panic, making

the boat more likely to sink. But if one person

aboard could remain lucid and calm, knowing

what to do and what not to do, that person

could help the boat survive. Their voice and

body would communicate clarity and calm;

people would trust them and listen to what

they had to say. One such person can save

the lives of many. Our world is something like

a small boat. Compared with the cosmos, our

planet is a very small boat. We may be about

to panic because our situation is no better than

that of the small boat in the sea. Humankind

has become a very dangerous species. We

need people who can sit still, are able to smile,

and can walk peacefully in order to save us. In

my tradition it’s said that you are that person,

that each of us is that person.

Having served three years, I felt that it was time to place the baton into Gwynn's very capable hand. Gwynn who was Poet Laureate back in the day, accepted with enthusiasm. She'll do a fantastic job! - Ed Coletti

And from Gwynn, Dear Poetry Fans and Newcomers,

Our first 2025 reading at Cafe Frida Gallery, 300 South A Street, Santa Rosa, on the outdoor stage, will take place on Sunday,

March 30th at 1 pm. Any of you who have attended know this series to be a joyful festival that Ed Coletti began following the height of the pandemic when poets and audiences were hungry to get out and mingle. Each subsequent gathering has been similarly well-received by large (at least by poetry reading standards) audiences. Come one, come all! This year’s additional Festival readings will be on June 29th and September 28th. As we enter the Festival’s 4th year, Ed Coletti is moving on to other things, and has entrusted this valuable enterprise to me. I am honored and I will do my best. We will all miss Ed as instigator, curator and MC, but he will be one of the readers at the next Cafe Frida Poetry Festival on June 29th. I’m pleased and proud to present the reading order of the terrific poets for March 30th: —Gwynn O’Gara (Ed had a hand in this.)

—Bill Greenwood

—Rita Losch

—Karl Frederick

—Shawna Swetech

—Chris Giovachini

—Susan Lamont

—David Madgalene Hope to see you on the 30th, and please say Hi. There are many of you I don’t know and would like to (“friends I haven’t met yet” as Gene Ruggles would say). Consider arriving early for lunch and great music! Cheers to all, Gwynn O'Gara

AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT

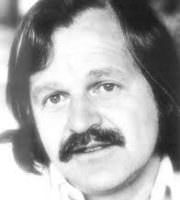

Charles Bukowski

If you're losing your soul and you know it, then you've still got a soul left to lose.

-Charles Bukowski

Trashcan Lives

the wind blows hard tonight and it's a cold wind and I think about the boys on the row. I hope some of them have a bottle of red. it's when you're on the row that you notice that everything is owned and that there are locks on everything. this is the way a democracy works: you get what you can, try to keep that and add to it

My personal experience with the work of Bukowski began somewhat naively as expressed in my own poem

"Ed Coletti’s poem is a boozy nod to Bukowski’s busted saints and spider-veined 'glory,' significantly asking “Is this poetry?”-- before answering with a resigned grin and sinking into ultimate pleasure." -- XCarl Macki

Bukowski Sometimes Makes Me Happy

at a small college near the beach

sober

the sweat running down my arms

a spot of sweat on the table

I flatten it with my finger

blood money blood money

my god they must think I love this like the others

but it's for bread and beer and rent

blood money

I'm tense lousy feel bad

poor people I'm failing I'm failing

a woman gets up

walks out

slams the door

a dirty poem

somebody told me not to read dirty poems

here

it's too late.

my eyes can't see some lines

I read it

out-

desperate trembling

lousy

they can't hear my voice

and I say,

I quit, that's it, I'm

finished.

and later in my room

there's scotch and beer:

the blood of a coward.

this then

will be my destiny:

scrabbling for pennies in tiny dark halls

reading poems I have long since become tired

of.

and I used to think

that men who drove buses

or cleaned out latrines

or murdered men in alleys were

fools.

*******************

damned things ever,

the gathering of the clansmen and clanladies,

week after week, month after month, year

after year,

getting old together,

reading on to tiny gatherings,

still hoping their genius will be

discovered,

making tapes together, discs together,

sweating for applause

they read basically to and for

each other,

they can't find a New York publisher

or one

within miles,

but they read on and on

in the poetry holes of America,

never daunted,

never considering the possibility that

their talent might be

thin, almost invisible,

they read on and on

before their mothers, their sisters, their husbands,

their wives, their friends, the other poets

and the handful of idiots who have wandered

in

from nowhere.

I am ashamed for them,

I am ashamed that they have to bolster each other,

I am ashamed for their lisping egos,

their lack of guts.

if these are our creators,

please, please give me something else:

a drunken plumber at a bowling alley,

a prelim boy in a four rounder,

a jock guiding his horse through along the

rail,

a bartender on last call,

a waitress pouring me a coffee,

a drunk sleeping in a deserted doorway,

a dog munching a dry bone,

an elephant's fart in a circus tent,

a 6 p.m. freeway crush,

the mailman telling a dirty joke

anything

anything

but

these.

Writing Instructions

.jpg)

Robert Graves to Alastair Reed

"I confessed the difficulty of putting the images I saw into adequate words, and he nodded eagerly. 'This is, my dear, the work before us, always. To find a language adequate to what is revealed. I’m glad you know this. I feel the same consternation quite often, trying to attach feelings to words, to summon the image and declare it pure.'” -(quote from Borges in Jay Parini Borges and Me pg162

"I confessed the difficulty of putting the images I saw into adequate words, and he nodded eagerly. 'This is, my dear, the work before us, always. To find a language adequate to what is revealed. I’m glad you know this. I feel the same consternation quite often, trying to attach feelings to words, to summon the image and declare it pure.'” -(quote from Borges in Jay Parini Borges and Me pg162**********************

Fran Claggett's Tribute Causes Me to Blush

Felicity du Fleur, at a poetry reading

Just the other day, at a poetry reading

organized by our own Ed

Coletti at the

Frida Cafe, yes, that Frida,

we see her

always in pain in her art,

married to

Diego, but he had nothing to

do with

her pain, well, we don't

know, do we.

but she gave her name to this

cafe, made for

poetry, with a stage and

shade, just perfect,

anyway, as I was saying, the

other day,

Sunday, it was, the poetry

lovers of Sonoma

were there to hear some of

our wonderful

poets, well, Ed himself, read

and I must tell

you, his poems were, well,

simply said, the

absolute best we heard all

afternoon, so good

I can't wait to read them in

print, not only the

one about crows, since he and

I both know that

is a winner, but the second

one, and I can't recall

the title, but it was, well,

just great, a totally fine

poem and I should know,

because although my name

is Felicity du Fleur, it

might as well have been

Felicity du Poetas because I

know a great poem

when I hear it and I heard Ed

read it last Sunday,

but what I really want to

tell you today is that

every time I lifted my eyes

to the wall, the WAll

at the entrance of the Cafe,

the whole wall, the

entire bank of it was

shimmering with a deep deep

beyond the pale purple flower,

an absolute purple

totally covering the

wall...on and on, as far as the

wall went, as far as Ed's

poem took me,

Felicity du Fleur/Poetas at

this, Frida's purple cafe.

Felicity du Fleur

aka fran

claggett-holland

The Fifth Day

On the fifth day

the scientists who studied the rivers

were forbidden to speak

or to study the rivers.

The scientists who studied the air

were told not to speak of the air,

and the ones who worked for the farmers

were silenced,

and the ones who worked for the bees.

Someone, from deep in the Badlands,

began posting facts.

The facts were told not to speak

and were taken away.

The facts, surprised to be taken, were silent.

Now it was only the rivers

that spoke of the rivers,

and only the wind that spoke of its bees,

while the unpausing factual buds of the fruit trees

continued to move toward their fruit.

The silence spoke loudly of silence,

and the rivers kept speaking

of rivers, of boulders and air.

Bound to gravity, earless and tongueless,

the untested rivers kept speaking.

Bus drivers, shelf stockers,

code writers, machinists, accountants,

lab techs, cellists kept speaking.

They spoke, the fifth day,

of silence.

- Jane Hirshfield